The most recent IPCC report is comprehensive, impressive, frightening, and a monument to both the scientific endeavor and humanity’s own ability to analyze and interpret what our planet is telling us. But it is not perfect, and here we want to touch on four key questions that arose as we read through it.

Note: this essay was co-written by me and Samantha Snedeker, an Amasia Fellow in our Fall 2021 cohort. My thanks to her for exceptional work!

What’s this all about then?

The IPCC is the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, composed of a group of highly qualified scientists from around the world. Every 6-7 years, this group releases a series of reports offering a comprehensive assessment of the state of climate change.

IPCC reports don’t produce any new evidence, but rather compile all the most recent data from existing scientific publications. The reports provide a birds-eye view of the scientific consensus and are our leading barometers on the state of the climate crisis.

The IPCC recently released the Working Group 1 contribution to its Sixth Assessment Report. This contribution made available on August 7th, is the first of many to come as a part of the sixth assessment cycle, and presents a comprehensive understanding of the physical basis of climate change. This means, in other words, a purely scientific description of the current state of the climate.

There are important differences between this report and those that have come before it. For one, the information presented in this report is more accurate and reflects a newfound clarity that its predecessors lacked. As a result, the IPCC is able to state that it is “unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land,” (IPCC page 6).

Never before has the IPCC been able to make such a strong claim.

Nothing is perfect, so we have four critiques to offer:

1. Where is our favorite legal fiction, the “corporation” (= businesses)?

The IPCC appears to leave out entirely the corporate world in the report. We think this is a mistake, even in a report that is all about the science.

In an effort to present the physical basis for the current state of the climate, the report doesn’t contextualize the causes and contributors of climate change. Yes, human-induced greenhouse gas emissions drive climate change, but what drives human-induced greenhouse gas emissions?

Corporations are one of the main vehicles whereby our species actually drives greenhouse gas emissions. A 2019 study from the Climate Institute found that 20 companies account for more than a third of all energy-related GHG emissions dating back to 1965. Businesses (a) are substantial direct emitters of greenhouse gasses and (b) through a variety of mechanisms including advertisements, sponsorships, and branding techniques, play a large role in human buying behavior.

We know that consumption-centered human behavior greatly impacts climate change. The carbon footprints created through household consumption and clothing consumption are just two examples of how individuals and industry combined can harm the environment.

With corporations and businesses serving as such large emitters of GHG gasses yet absent from the report, the IPCC report doesn’t quite capture the nuances of “causality.” The IPCC missed an opportunity (in our opinion) to address those individuals and institutions with some of the most critical roles to play in helping to fight warming and the fatal consequences of a changing climate.

The issue is more deep rooted — this report is primarily shared with governments and policy makers. It should be on the desk/inbox of every CEO of a Fortune 2000 company (and beyond).

2. The extremes are going to kill us — and they’re going to kill us in our cities

The IPCC report is 3,949 pages. It’s not a quick read, nor an easy one, which makes it difficult to extract the most important information presented. We thought two points should have been emphasized much more vigorously: (a) the implications of increased climate extreme events; and (b) the idea that cities will become hotspots for worsening climate effects.

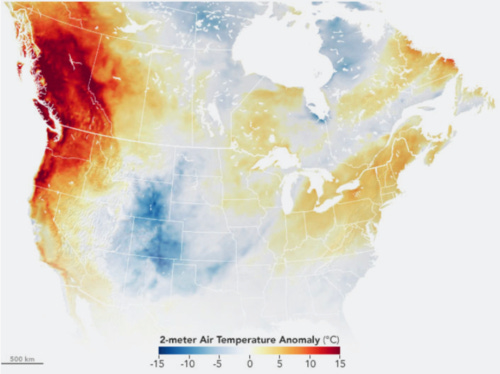

Figure 1: Heatwaves in June in the Pacific Northwest, cited as impossible to occur without climate change.

From 2000 to 2019, extreme weather has accounted for more than 9% of global deaths, with the number of deaths caused by extreme heat rising. The case of extreme heat is particularly dangerous to vulnerable populations without access to air conditioning or for those who are unable to seek help in the face of such a crisis.

These are consequences that we have already felt in cities like Portland, Oregon where such high temperatures would have been virtually impossible without human-induced warming.

The deadly results of extreme events have limited visibility in the report. As a result, the IPCC could be contributing to a phenomenon called human simplification, where individuals make choices based on the low risk of individual events, without considering changes in the overall risk distribution as a result of increasing extremes.

By nature of being an “extreme” event, these types of situations may not happen very often; however, when they do, they have consequences more intense than many people may realize.

Separately: greater than half of the global population is concentrated in urban areas and is thus susceptible to worsening climate extremes that arise as a result of urbanization. The report cites cities as areas of human-induced warming with intensified heat waves, tropical cyclone storm surges, and rainfall. The report also addresses the urban heat island effect, which explains why urban spaces can be many degrees warmer in both the day and night than their surrounding areas.

Putting these two issues together: we thought that the report could have done more to emphasize the necessity for cities and really any impacted region to prepare for extreme events. Lacking infrastructure to properly handle even a single climate event, such as a flood, heat wave, or tropical storm, can result in devastating and long-lasting impacts.

We’d have asked for a greater focus on explaining extreme events because our preparation for “climate adaptation” unfortunately requires being in a position to deal with the extremes, not be comforted by averages.

3. The good stuff is coming… but we should have read about some of it now

The IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report will consist of the contributions from three working groups. The Working Group 1 contribution is titled: The Physical Basis for Climate Change (this is the piece we’ve been analyzing).

The next two working group contributions have been delayed as a result of COVID-19, and are anticipated to be released in 2022. The Working Group II contribution will be titled Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability and the Working Group III contribution will be titled Mitigation of Climate Change.

The Physical Basis for Climate Change is essentially the “what” of climate change, and presents data points like mean precipitation change and increase in greenhouse gas emissions across various regions. However, there is no mention as to (a) why these things are happening and (b) what we can do about it. That is out of scope for this report.

The later reports will focus on those other aspects of climate change, in addition to providing suggestions and solutions to fight these problems. Their outlines suggest a stronger focus on the broader, cultural basis for much of the evidence presented in the first report.

For example, Mitigation of Climate Change will have chapters dedicated to fighting climate change in urban spaces through industry and policy. Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability will have chapters dedicated to exploring the impacts of climate change on different socioeconomic groups as well as addressing future risks and ways to handle these risks. A final draft of this report has already been sent to governments for comment. However, versions of these reports have not yet been made available to the public.

These later documents will bring much-needed context to the data that is presented in this first report and provide actionable items for those seeking to fight the climate crisis. But the IPCC, in our view, really missed a trick by not providing “previews” of future reports. This could have greatly reduced the sense of defeatism that we feel pervades much of the report, which brings us to our last critique.

4. The paradox of choice and defeatism

The paradox of rational choice provides a clue as to why many people, despite (or due to) understanding the detrimental impacts of climate change, fail to individually make sustainable choices. I have written about the paradox of choice here.

Countering this paradox requires an emphasis on the tangible impact of an individual’s set of actions in the face of climate change. The IPCC report, inadvertently, does the opposite.

The report places repeated emphasis on the notion that greenhouse gas levels and surface temperatures will continue to persist for centuries. Various articles that came out in response to the report highlighted persisting changes as one of the report’s key takeaways. This emphasis on irreversible change, amplified throughout external sources, can give rise to a sense of defeatism where individuals feel that their actions have an ultimately trivial impact on climate change.

I confess this is especially painful for us at Amasia, because we believe that behavior change at scale is the only way to address the current state of the climate (learn more about why we think this way here: Amasia Investment Thesis).

Individual actions have never been more important as we need to act immediately to reduce the worst effects of greenhouse gas emissions. This means we need swift and widespread behavior change, at the level of the individual, to limit warming from reaching more troublesome thresholds, such as 2 or 3 degrees Celsius.

In Closing

The IPCC is doing tremendously important work -- arguably the most important work there is -- in presenting comprehensive analyses of the climate system. We’re not complaining -- rather we offer these comments in an attempt to make future reports better.

More Readings

Amasia

In Our Hands: How We Got Here and How We Change

Amasia and the Climate Crisis, ⅓: The Facts

Amasia: Investing to Make the World Safer

IPCC Report

IPCC Explainers

The Repercussions of a Changing Climate

What Scientists Are Saying About the UN Climate Report

Solutions

Energy is at the heart of the solution to the climate challenge

Per Espen Stoknes: What Holds Us Back From Facing The Threats of Climate Change Transcript

Lessons for climate policy from behavioral biases towards COVID-19 and climate change risks